Alcohol and drug abuse is one of the fastest growing healthcare problems for Americans 60 years and older.

Source: SAMHSA

According to the World Bank, from 2010-2014, Americans aged 65 and older made up 14 percent of the total population. Japan was ranked the highest at 26 percent.[1] Numerous issues affect the aging population in the US, including physical decline, disease, depression, dementia, falls, abuse/neglect, financial vulnerability, and polypharmacy.[2] The age-involved problems older Americans face places them at a risk for substance abuse.

Senior substance abuse conflicts so deeply with the average perception of older Americans that it seems oxymoronic. However, senior substance abuse is a formidable problem within the nation’s drug abuse and addiction crisis.

Substance Abuse in Older Americans

The National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence has collected data on the prevalence of drug abuse among older Americans. The following highlights of substance abuse and treatment in this group are insightful:

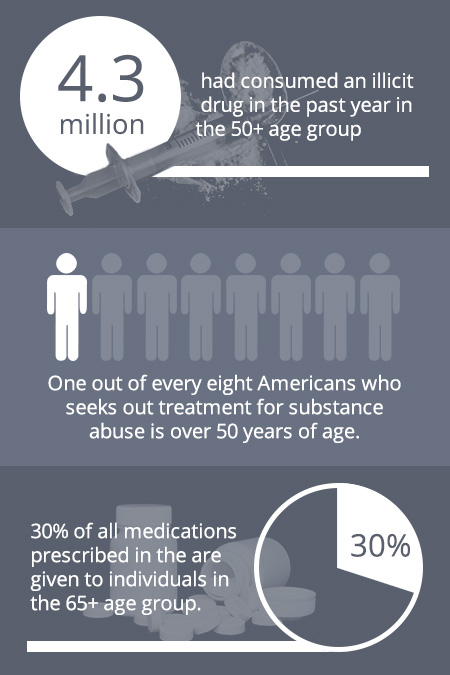

- According to a 2008 survey, in the 50+ age group 4.3 million had consumed an illicit drug in the past year.

- Regarding drug recovery treatment admissions in the 50+ group, from 2000-2008, there was a 70 percent increase even though this population only grew by 21 percent over this time period.

- Of all medications prescribed in the US, 30 percent are given to individuals in the 65+ age group.

- One out of every eight Americans who seeks out treatment for substance abuse is over 50 years of age.[3]

Substance abuse presents numerous hazards in older populations. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the following are some of the ways in which substance abuse is an especially complex problem for the older population:

- Drugs can interact with geriatric physiology in more complicated and dangerous ways compared to how they act in younger body systems.

- There is an escalated risk of sickness, falls, injuries, and financial instability in the older population.

- Alcohol abuse causes an acceleration in physical decline in seniors.

- If left untreated, symptoms and side effects will worsen over time and can compound any other age-related health conditions.[4]

According to the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence, 9 percent of Medicare recipients aged 65 or older reportedly consume more than 30 drinks in one month. The number of drinks consumed in a week, among other factors, is clinically relevant when diagnosing a person with an alcohol use disorder per the guidance set forth in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5). When older Americans seek recovery services, four out of five of them require treatment for alcohol abuse compared to abuse of other drugs.

Source: NCADD

An ageing population with substance abuse treatment needs is an increasingly pressing issue. Projections of the problem estimate that by the year 2020, in the 50-or-older age group, the number of people who need treatment for substance abuse and addiction will double.[5] As family members play a critical role in bringing people in need to treatment as well as providing senior care, they will increasingly need guidance on rehab services.

Signs of Drug Abuse Among Older Individuals

Ageing is associated with a host of physical and psychological changes that can make it all the more difficult to detect substance abuse. The following are some potential signs that an older person has a problematic relationship with prescription medications (includes sedatives, stimulants, and pain relievers) in specific:

- Regarding prescription pills, an older person obtains prescriptions for the same medication from more than one doctor and/or fills prescriptions for the same medications at different pharmacies.

- The individual demonstrates a preoccupation with taking medication, hides medication, stockpiles medication, and/or has a fear of not having access to medication.

- The person defends pill-related practices, such as taking more of the medication or using more often than advised.

- The individual shows behavioral changes, such as becoming uncharacteristically withdrawn, irritable, or angry when there doesn’t seem to be an environmental reason to act this way.

In addition, as retired Americans typically have fixed incomes, off-budget spending can be a tipoff of substance abuse. To obtain extra prescription pills, a person may go out-of-pocket to visit a doctor (to avoid double billing to Medicare or other insurance), or purchase these drugs from the street or online, in some cases. Black market prices vary by locale, but according to one information site 2 mg of Xanax (a sedative) can cost as much as $7 on the street and 10 mg of Opana (a pain reliever) can be as much as $40.

Sources: Family Doctor, StreetRx

Older Americans and Prescription Drug Abuse

In the 60+ demographic, research shows that as much as 17 percent of people in this group abuse prescription medications.[6] Abuse of this class of drugs does not typically start with the intention to do so. Older individuals face a host of medical conditions that can result in receiving a lawful prescription for a prescription medication (most often a pain reliever or sedative, but some may receive a stimulant medication such as Adderall for ADHD).

In fact, seniors consume a relatively high number of prescription pills each day. Although not all of their daily drugs are addiction-forming, the familiarity with pill-taking may lead to older individuals having a benign association with them. However, prescription sedative, stimulants, and pain relievers have moderate to high addiction profiles.

Within the prescription pill matrix, there is a growing concern about older individuals and prescription opioid abuse. In general literature, there is often a lack of clarity on the difference between opiates and opioids. Opiates are organic compounds that derive from opium, which is cultivated from the poppy plant. Morphine is an example of an opiate. Heroin is sometimes referred to as an opiate, but the National Institute on Drug Abuse considers it an opioid. Opioids are synthetic or semi-synthetic drugs that are designed to mimic the chemical structure of opium in order to have a pain-relieving effect.[7] Opioids include heroin and prescription pain relievers, such as oxycodone (branded drugs include OxyContin and Percocet), hydrocodone (e.g., Vicodin), and codeine.

According to Medicare information released in 2014, 8.5 million individuals in the 65+ age group had prescriptions for opioids.

Source: Aljazeera America

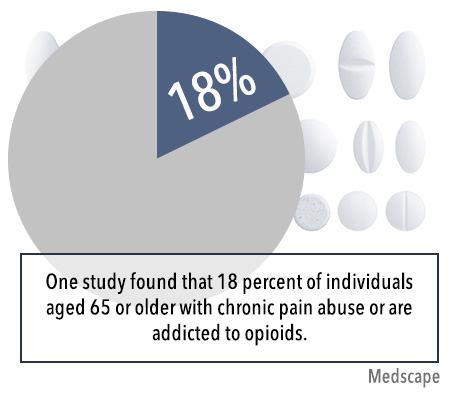

Older Americans may receive lawful prescriptions for pain relievers for any number of medical reasons, including post-surgery, after a physical trauma such as a fall, for pain related to cancer, for conditions such as gout, and general chronic pain. In view of the addiction profile associated with opioids and social factors common to older communities, such as physical pain and/or loneliness, it is not surprising that one study found that 18 percent of individuals aged 65 or older with chronic pain abuse or are addicted to opioids.[8] An added danger is that, compared to other groups, seniors have the highest rate of death due to a drug overdose, which in part involves the use of prescription opioids.[9]

Referred to in some reports as a “hidden epidemic,” there is a compelling and well-founded concern that senior drug abuse does not receive adequate attention due to the traditional attitudes toward this group as being too old and too wise to abuse drugs. However, physical dependence and addiction can set in to an older person’s body and psyche as much as a younger person’s. But in the case of older individuals, the consequences can be more hazardous.

First, in older persons, bodily functions are not operating at optimal levels, which can make drug use even more dangerous. For example, an older liver generally has reduced capabilities that can lead to greater drug toxicity in the body. Treatment may be delayed as older individuals may feel ashamed to report their concerns about their drug use behaviors to loved ones. As this population has legitimate opioid prescriptions for pain management, there is concern about how to effectively treat pain after abuse activities develop. Effective drug recovery services must necessarily address issues in geriatric health as well as provide addiction treatment.

How to Help an Older Person

In the event that a person suspects that an older person is abusing drugs, the first step is typically to collect relevant information in order to make an informed decision about next steps to take. A concerned person’s access to information depends in part on whether the older individual is independent or under care. Those who serve as an older person’s formal or informal guardian will have access to medical and financial information.

A review of prescriptions (inventory taking) will reveal helpful information, including the prescribing doctor’s information, the type of medications taken, and which pharmacy refills them and how often. If the older person is independent, a concerned person may want to draft a list of concerns and address them in an informal conversation. The best practice is to have the conversation when the older person appears lucid and not experiencing any psychoactive effects of any drugs, prescription or otherwise. In more severe cases, a formal intervention and an immediately actionable rehab plan may be necessary.

There are numerous steps that can be taken between having a suspicion of drug abuse and having a talk or organizing an intervention (if needed). An advice site for caregivers provides the following helpful guidance:

- Confer with the senior’s doctor to learn if there are safe and effective alternatives to the current pain medications.

- Determine if there are any physical or psychological side effects of substance abuse present.

- Help to educate the senior on the health risks associated with opioid and other drug abuse, including withdrawal effects.

- Help the senior to provide attending doctors with a full list of all medications currently being taken.

- Learn about stressors and other contributing factors that could be influencing or driving the drug abuse.

- As needed, encourage and help the senior to seek structured treatment services at a rehab center.

- Remain engaged as withdrawing from the problems will likely only escalate the risks for the senior.

- Learn about insurance coverage or other payment options for a rehab treatment stay and organize admission as necessary.[10]

A compulsive need to consume drugs may eventually overtake an older person who did not start out with an abuse intention. Despite an older person’s specific pathway to substance abuse, once it occurs, treatment is advisable, not only to address present needs but also to prevent a worsening of this condition. In terms of recovery rates, older Americans have outcomes that are as good as or better than younger individuals.[11]

Treatment

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, substance abuse treatment approaches that are used in younger populations have also proven to be effective for older populations.[12] Viewed from a wide angle, there are two main components to substance abuse treatment: targeted medications and therapy.

Targeted medications are currently only available for the treatment of abuse of opioids, alcohol, and/or nicotine. At present, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved any medications to assist the recovery process from stimulants, marijuana, or depressants.[13] Poly-drug abuse can be unbundled from a treatment perspective; for example, a person who abuses both opioids and benzodiazepines (e.g. Xanax) may still receive targeted medications to treat opioid abuse even though no medications are available for benzodiazepine abuse.

In view of the statistics discussed earlier, seniors are particularly susceptible to opioid abuse, but, if they do seek recovery services, targeted medications are a treatment possibility. Currently, the available medications are methadone, buprenorphine (e.g., Suboxone or Subutex), and naltrexone. These medications can be used during the withdrawal phase (as part of a tapering process) as well as during the abstinence maintenance phase. In a rehab setting, the specific dosages for tapering and maintenance will be determined by medical staff members as part of a comprehensive recovery treatment plan.

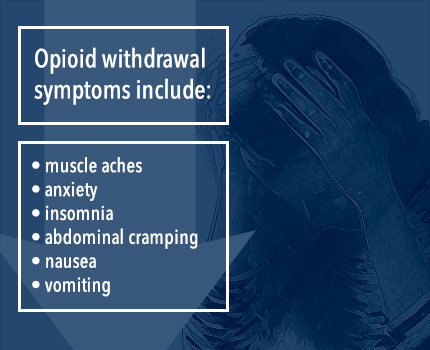

Opioid withdrawal is associated with numerous withdrawal symptoms, including muscle aches, anxiety, insomnia, abdominal cramping, nausea, and/or vomiting.[14] In addition to the discomfort or pain of the withdrawal process, cravings may arise. This is a potentially risky phase of recovery, as these withdrawal effects can lead to relapse as a coping strategy. A supervised medical detox can provide not only medications but also the additional safeguard of supervision (i.e., 24/7 supervision in an inpatient program and partial supervision in an outpatient program).

After detox, a person recovering from opioid abuse may begin abstinence maintenance therapy on methadone, buprenorphine (typically Suboxone), or naltrexone. As seniors may face mobility or transportation issues, Suboxone may be the most convenient medication to use. Whereas methadone must be dispensed at approved facilities, Suboxone can be taken at home by prescription.

Older Age and Substance Abuse in Film

Famed actress Ellen Burstyn, starring as the amphetamine-addicted Sara Goldfarb in Requiem for a Dream, played the role to harrowing effect. Although fiction, Sara’s storyline illuminates how drug addiction in older individuals can begin without abuse potential. The film captures Sara’s loneliness as she is a widow and her son is addicted to drugs. After Sara is invited to be a contestant on a game show, she becomes hooked on diet pills in hopes of regaining her youthful figure for the cameras. Ultimately, Sara descends into an amphetamine-induced psychosis attended by frightful hallucinations. Burstyn’s reprisal of a Sara, an “everywoman,” is highly relatable to any person despite her character’s advanced degree of addiction and mental collapse. The movie, as well as Burstyn’s performance, was exceptionally well-received among critics and the public.

Source: CNN

Another potential benefit of targeted medications is that they can help to keep recovering persons engaged in treatment. These medications require ongoing doctor or clinic visits and drug testing. In addition to speaking with medical staff, recovering persons can discuss any thoughts and feelings they have regarding their medication and the recovery process overall during therapy sessions. Medications are always used in combination with therapy. It is well-established that detox and maintenance therapy alone are not sufficient for recovery treatment.

Recovering seniors who are in treatment for substances other than opioids or alcohol will be treated with therapy. There are different therapeutic approaches in use across rehab centers, but behavioral therapies are among the most widely applied. Behavioral therapy approaches were conceived, in large part, to help clients replace self-destructive behaviors with healthy ones and to develop healthy ways to cope with stress. Studies of the effectiveness of behavioral therapy most often make an assessment vis-à-vis a particular drug of abuse.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, studies show that the following behavioral therapies have benefits for the drug of abuse indicated:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): nicotine, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and methamphetamine

- Motivational Interviewing/Contingency Management: nicotine, alcohol, opioids, stimulants, and marijuana

- Motivational Enhancement Therapy: nicotine, alcohol, and marijuana

- 12-Step facilitation: alcohol, opioids, and stimulants (among other substances of abuse)

- The Matrix Model: stimulants[15]

Recovery is a long-term process, irrespective of the recovering person’s age. After graduation from an intensive program, whether inpatient or outpatient, the largely self-directed aftercare process begins. Recovery meetings, 12-Step or other types, are considered to be a staple of aftercare. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) groups hold thousands of meetings across the US. The availability of different meeting options is particularly important for older Americans. According to Addiction Professional, seniors in AA show a preference for daytime meetings due to issues such as reduced ability to drive at night.[16]

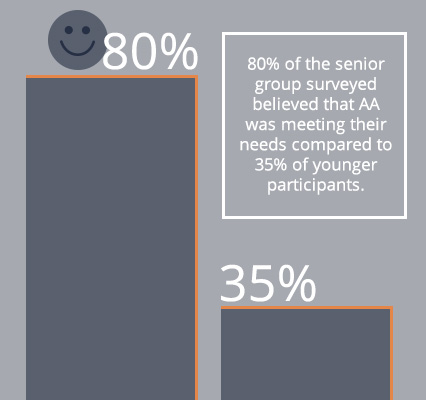

According to one study that included seniors and younger participants, the senior participants were overwhelmingly supportive of AA. Regarding the effectiveness of AA to help achieve sobriety, all the seniors answered positively compared to 75 percent of younger participants. Also, 80 percent of the senior group surveyed believed that AA was meeting their needs compared to 35 percent of younger participants. Lastly, on a 10-point scale, the senior group rated their overall satisfaction with AA a full point higher than younger participants.[17]

Although characterized as “hidden epidemic” in the media and among some governmental authorities, senior substance abuse needn’t be kept in the shadows, as many treatment options exist. Further, Medicare is available to help support the recovery needs of older Americans. Medicare will assist in the payment of treatment for alcohol or drug abuse in either an inpatient or outpatient setting, provided the facility participates and a doctor deems the services to be medically necessary.[18] The availability of programming and coverage can lower or eliminate barriers to entry. Whether older persons are living independently or receiving care from a loved one or third party source, it is never too late to start the recovery process.

As a generation of Americans grows older, the number of their health concerns increases. One such concern, which may come as a surprise to many, is substance addiction. But with aging bodies and aging minds, senior citizens developing an unhealthy dependence on their prescription meds is a realistic concern for their caregivers. Understanding how to use Medicare to pay for addiction treatment will answer many questions on the way to getting therapy.

An Overview of Medicare

Medicare was established in 1965 by President Lyndon B. Johnson, as a federal program to provide health insurance for seniors. Medical News Daily further explains that Medicare pays for hospital and medical care not only for senior citizens, but also for disabled people who meet certain criteria.[19]

Medicare has two components: Part A and B, which covers hospital and medical insurance, including hospital rooms (and other items, like meals, supplies, and tests). Part A also deals with healthcare based out of the home, such as physical, speech, or occupational therapy provided part-time and only if considered medically necessary.

If a patient requires care in a specialized nursing facility, or if the patient needs wheelchairs, walkers, and other medical equipment (and such a need can be demonstrated), then Part A will also insure the related costs.

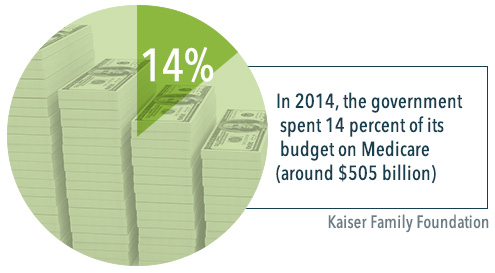

Since Part A is funded via payroll taxes, it is typically available to patients without the necessity of paying a monthly premium, as would be the case for private insurance plans. In 2014, the government spent 14 percent of its budget on Medicare (around $505 billion).[20]

Medicare Parts B, C, and D

Part B of Medicare is also known as Supplementary Medical Insurance. This pays for physician visits that are medically necessary, as well as outpatient hospital visits, home healthcare, and over services that benefit senior citizens and certain disabled Medicare patients. Such services might include:

- X-rays and laboratory tests

- Specified vaccinations

- Specified ambulatory services

- Blood transfusions

- Renal dialysis

- Outpatient hospital services

Unlike Part A of Medicare, Part B requires a monthly premium. Forbes magazine writes that the 2015 premium for most patients is $104.90 per month, while some seniors will see an increase of 16 percent in their premiums (which will require them to pay $121.80 every month).[21] Patients are not required to enroll in Part B.

Medicare Part C plans (also known as Medicare Advantage Plans, or Medicare + Choice) allow patients to tailor a plan that fits their medical needs. Part C works with private insurance companies to provide a portion of the coverage, meaning that health maintenance organizations or preferred provider organizations might work with the government program to devise a healthcare plan or provide specialist services to qualifying patients.

Medicare Part D was added to the program in 2006, and is a prescription drug plan. The drugs are administered by private insurance companies that each provide a plan with their own drugs and costs. A patient who wants to participate in Part D will have to pay both a premium and a deductible. The system is set up so that 75 percent of the drug costs are covered by Medicare, if the patient spends between $250 and $2,250 on drugs in a year. Medicare will further cover 95 percent of any amount over $3,600, but the amount between the $2,250 and the $3,600 cap is not covered.

Eligibility and Effectiveness

Eligibility for Medicare is determined by factors relating to age and health. A patient must be over the age of 65, or under the age of 65 and disabled, or of any age with end-stage renal disease (which is a form of permanent kidney failure that requires use of a dialysis machine, or a kidney transplant). Other restrictions include that the patient must be a citizen of the United States (or a permanent resident of at least five years), and be eligible for Social Security benefits.

According to Health Affairs Blog, Medicare is more effective than private insurance programs, in terms of controlling costs (Medicare premiums grew by 4.3 percent every year from 1997 to 2009, while private premiums increased by 6.5 percent per year during that time) and having lower overhead costs (with administrative expenses accounting for only 2 percent of operating budget).[22]

Medicare for Substance Abuse Treatment Payment?

Since Medicare is intended for senior Americans (or people with certain disabilities), the question of whether it can pay for substance abuse treatment may seem incongruous. However, addiction is a serious cause for concern for senior citizens. The National Institute on Drug Abuse has found that the same age bracket for Medicare (65 years or older) accounts for 11 percent of prescription medication abuse.[23]

The reasons for this are manifold. Senior citizens are prone to a number of mental health conditions, such as memory loss or dementia, that can compel them to take more of their medication than necessary (or healthy), unwittingly cultivating a dependency on the drugs. The physiology and metabolism of senior citizens change as well, meaning that even small or moderate doses can have the effect of a much stronger dose. A well-meaning prescription from a healthcare provider who does not realize this could result in a client becoming overmedicated and addicted.[24]

Fixed Income and Falling

Patients who are on a fixed income may not be able to afford their prescriptions, so they may “borrow” meds from friends or family members; however, this still constitutes a form of drug abuse, as the medications are not meant to be taken without a doctor’s prescription, and consuming drugs without proper medical oversight can have negative health effects (including addiction).[25]

Seniors also have more physical concerns than the general population – a result of their bodies requiring more care. Falling, for example, is not something that a senior can easily brush off; someone over the age of 65 has a greater risk of broken bones, fractured hips, and concussions, and the Medicare population requires hospitalization for physical injuries more so than any other age group.[26] Prescribing painkillers for this demographic comes with the risk of giving habit-forming drugs to people who are subject to significant risk factors for addiction. Over 20 percent of patients of Medicare age develop a substance use disorder, and in 2009, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration found that an increasing number of adults aged 50 and up were abusing drugs.[27], [28]

Paying for Addiction Treatment with Medicare

With addiction a serious concern for senior citizens, can their Medicare plans be used to pay for treatment? The short answer is “yes,” under the mental healthcare umbrella; but as with most government programs, there are caveats.[29]

The Livestrong Foundation explains that when it comes to inpatient alcohol treatment, “several conditions” must be met before Medicare coverage comes into effect. First, for example, the hospital or treatment facility must participate in Medicare (and thus has to meet Medicare standards). Secondly, a doctor or treatment specialist must affirm that the addiction treatment is medically necessary. Thirdly, the doctor/specialist must create a treatment plan that has to be approved by Medicare, before the program will pay for the addiction treatment.[30]

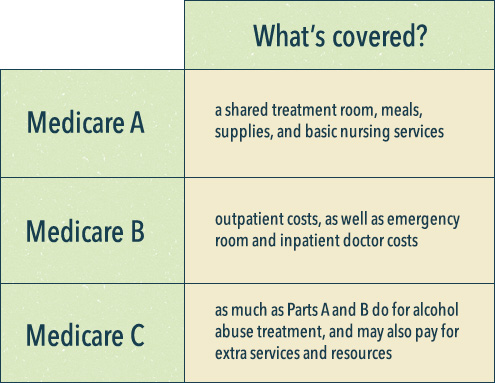

What’s Covered and What Isn’t Covered?

As per the different parts of Medicare mentioned earlier, Medicare Part A will cover a shared treatment room, meals, supplies, and basic nursing services. Part B pays for outpatient costs, as well as emergency room and inpatient doctor costs. Part C (the Medicare Advantage Plans) covers as least as much as Parts A and B do for alcohol abuse treatment, and may also pay for extra services and resources.

However, private rooms are not covered by Medicare plans, unless the doctor/treatment specialist makes the case that a private room is medically necessary for the client. Similarly, Medicare will not pay for private nursing costs or services that are deemed extraneous (such as having a television or telephone in the room).

Medicare Advantage plans are bought through private insurance companies, and those companies may have their own coverage policies. For instance, a client receiving inpatient alcohol treatment through Medicare Advantage should check the plan to see what degree of treatment is covered, as well as what amount of copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles have to be covered, wherever appropriate.

A further restriction on using Medicare to pay for addiction treatment is that if the treatment is to be delivered in a standalone psychiatric hospital, Medicare will only cover 190 days of treatment over the client’s entire lifetime. It is possible for a client to transfer to a general hospital to continue their psychiatric treatment (after their 190 days are up), at which point Medicare will offer coverage for an unlimited duration; the length of psychiatric treatment is only curtailed if the client receives treatment in a dedicated psychiatric rehabilitation center.[31] The cap has been met with criticism, with a policy lawyer for the Center for Medicare Advocacy calling it arbitrary, and saying that the cap targets people who have serious mental illness and are in urgent need of care.

An Improving Proportion of Coverage

When it comes to addiction treatment, the Medicare program does not cover a specific range of healthcare services – only a portion of the total healthcare cost will be picked up by the program. That portion is currently 80 percent of the approved amount for mental health treatment services, such as alcohol and drug addiction treatment (after the $147 Part B deductible has been met). The client and the supplemental insurance provider are required to pay the remaining 20 percent.[32]

The coverage is an improvement on previous years, when Medicare covered as little as 50 percent of mental health treatment bills. The passage of the Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act sought to redress the disparity, by giving mental health concerns the same level of insurance coverage as other medical issues would receive (similar to how the Mental Health Parity and Equity Act, which prohibits group health plans and health insurers from unfairly charging more for mental health or substance use disorder benefits, and not extending those costs to medical and surgical benefits).[34], [33]

Medicare Certifications

The Huffington Post explains that if a client decides to consult a nonmedical doctor (like a psychologist or a clinical social worker), that healthcare professional has to be certified by Medicare or has to take assignment (they accept Medicare’s approved coverage as the full payment amount). If neither condition is met, Medicare will not pay for the service.

Medicare will cover the services of nonmedical doctors who are certified by Medicare who do not take assignment, but these doctors may charge a client up to 15 percent over Medicare’s approved coverage amount, in addition to the 20 percent coinsurance, which the client would be responsible for.[35]

The Affordable Care Act and Paying for Substance Abuse Treatment

The idea of making mental healthcare and addiction treatment available to more people was a point of inclusion in the Affordable Care Act. The White House’s Office of National Drug Control Policy writes that one of the 10 essential health benefits is the treatment of substance use disorders, so much so that all health insurance plans sold through the Health Insurance Exchanges have to include options for treating addiction.[36]

In explaining “How Obamacare is Changing Addiction Treatment Coverage,” The Huffington Post spoke to an employee benefits attorney, who called the new policies “a sea change” in how health plans deal with covering issues of mental health and addiction treatment benefits. The Affordable Care Act’s rulings on parity – giving mental health coverage the same proportion of benefits as surgical or medical treatment – will provide 32 million people access to substance abuse and mental health treatment, and 31 million people will receive expanded mental health and substance abuse benefits, according to the US Health and Human Services Department.[37]

Under the Affordable Care Act:

- Pre-existing mental health conditions are covered.

- Insurance plans must offer parity between mental health treatment and medical/surgical treatment.

- Out-of-pocket spending is limited ($6,350 for individuals and $12,700 for families, for medically necessary treatment).

- Prescription drugs must be covered by insurers.

- More people have been getting treatment (47 million people did not have health insurance in 2012).

- Hospitals and treatment facilities are struggling to keep up (rural areas in particular do not have the personnel to service patients who otherwise qualify for mental health treatment).

The Road Ahead

The last point hints at the biggest problem facing the law: There still remains a vast amount of work to be done. In pointing out that more than $2.6 trillion is spent every year on healthcare, The Fiscal Times laments that “only a small fraction” of that amount is allocated to the treatment of mental health issues and substance use disorders. Even with the noble overtures of the Affordable Care Act, the national director for policy and legal affairs at the National Alliance of Mental Health notes that the healthcare problems surrounding the treatment of mental health cannot be solved by the act, and that people will still struggle getting the required coverage for their concerns.[38]

To that point, USA Today notes that a federal Medicaid law that limits available treatment beds across the country is a “serious impediment” to ensuring widespread access to addiction treatment. The law stipulates that drug treatment centers that have over 16 beds cannot bill Medicaid for inpatient services provided to low-income adult patients. The restriction was implemented in order to prevent Medicaid funding from going to private treatment centers that would place patients en masse in large, impersonal institutions.

The modern-day result of this law, however, is that drug rehabilitation centers are legally compelled to turn away new Medicaid beneficiaries who are actually entitled to their treatment under the Affordable Care Act.[39]

‘It Hasn’t Happened’

The Washington Post offered a damning verdict on the promises the Affordable Care Act made towards better mental healthcare coverage: “it hasn’t happened.” Quoting the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), the Post writes that the efforts to introduce parity between mental health and addiction treatment, and surgical and medical treatment, have only achieved mixed results; notwithstanding the mandate in theory, the parity does not exist in practice for the vast majority of uninsured Americans.

The study conducted by NAMI found that people are having difficulty finding therapists and other mental healthcare practitioners who participate in their health insurance plans. Patients also have to “clear multiple hurdles” in order to continue to receive their medication, sometimes paying higher out-of-pocket prices for their drugs.

Additionally, it is frequently difficult to obtain information about which services and treatments are insured, and which medical providers participate in mental healthcare networks, before a patient is actually enrolled. For some people, so much has to be paid out-of-pocket to get any kind of help for their addiction that treatment is rendered financially prohibitive.

One person explained that their insurance would pay their primary care doctor for a 10-minute appointment for the flu, more than it would their psychiatrist for an hour-long session. This, naturally, would make the psychiatrist less inclined to accept the client’s insurance.[40]

Despite the bureaucratic, legal and political hurdles, patients who are covered by the Affordable Care Act are benefitting from it. The director of business development for a treatment center in Illinois tells USA Today that even though patients don’t eagerly look forward to their addiction treatment, they are grateful to have the chance to pay for it. It’s an opportunity that they did not previously have, and that can make all the difference in the world.

Citations

[1]“Data: Population Ages 65 and Above (% of total).” (n.d.). The World Bank. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[2] Stibich, M. (Sept. 11, 2013). “Top Ten Aging Challenges.” About Health. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[3]“Seniors and Drugs.” (n.d.). National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[4] Substance Abuse Among Older Adults: An Invisible Epidemic.” (1998). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[5] “Seniors and Drugs.” (n.d.).

[6] Sollitto, M. (n.d.). “Seniors and Prescription Drug Addiction.” Aging Care. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[7] “Opiates/Opioids.” (n.d.). The National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[8] Lowry, F. (Dec. 13, 2012). “Prescription Opioid Abuse in the Elderly an Urgent Concern.” Medscape. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[9] “Doctor: Seniors Have ‘Highest Rate of Drug Overdose Death‘” (Aug. 26, 2015). Aljazeera America. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[10] Sollitto, M. “Seniors and Prescription Drug Addiction.”

[11] “Seniors and Drugs.” National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence.

[12] “Are There Specific Drug Addiction Treatments for Older Adults?” (Dec. 2012). National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[13] “Treating Substance Abuse.” (n.d.). NIH Senior Health. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[14] “Opiate Withdrawal.” (Apr. 3, 2013). Medline Plus. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[15] “Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide (Third Edition).” (Dec. 2012). National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[16] Cumella, E. and Scott, C. (July 31, 2014). “In the Experience of AA, a Member’s Age Matters.” Addiction Professional. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Medicare Coverage of Treatment for Alcoholism and Drug Abuse.” (n.d.). Medicare Interactive. Accessed Sept. 19, 2015.

[19] “What is Medicare? What is Medicaid?” (n.d.) Medical News Today. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[20] “The Facts on Medicare Spending and Financing.” (July 2015). The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[21] “It’s Official: Medicare Part B Premiums Will Rise 16 Percent in 2016 for Some Seniors.” (November 2015). Forbes. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[22] “Medicare is More Efficient than Private Insurance.” (September 2011). Health Affairs Blog. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[23] “Prescription Drug Abuse/Misuse in the Elderly.” (September 2008). Geriatrics. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[24] “Age-Related Physiological Changes and their Clinical Significance.” (December 1981). Western Journal of Medicine. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[25] “Older Adults.” (November 2014). National Institute on Drug Abuse. Accessed March 8, 2016.

[26] “Important Facts About Falls.” (September 2015). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[27] “Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume 1. Summary of National Findings.” (2010). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[28] “National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions.” (October 2006). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Accessed March 9, 2016.

[29] “Mental Health Care (Outpatient).” (n.d.) Medicare.gov. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[30] “Medicare Benefits for Inpatient Alcohol Treatment.” (December 2015). Livestrong Foundation. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[31] “Mental Health Care (Inpatient).” (n.d.) Medicare.gov. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[32] “Medicare Outpatient Mental Health Coverage Parity Begins Jan. 1, 2014.” (November 2013). APA Practice Organization. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[33] “The Mental Health Parity and Equality Addiction Act.” (n.d.) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[34] “Medicare to Cover More Mental Health Costs.” (December 2013). The New York Times. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[35] “How Medicare Covers Outpatient Mental Health Services.” (December 2014). The Huffington Post. Accessed March 9, 2016.

[36] “Substance Abuse and the Affordable Care Act.” (n.d.) Office of National Drug Control Policy. Accessed March 10, 2016.

[37] “How Obamacare Is Changing Addiction Treatment Coverage.” (March 2014). The Huffington Post. Accessed March 10, 2016.

[38] “6 Ways Obamacare is Changing Mental Health Coverage.” (November 2013). The Fiscal Times. Accessed March 10, 2016.

[39] “Despite Obamacare, a Gaping Hole in Addiction Treatment.” (April 2014). USA Today. Accessed March 10, 2016.

[40] “Obamacare Mandated Better Mental Health-Care Coverage. It Hasn’t Happened.” (October 2015). Washington Post. Accessed March 11, 2016.